Around the world there is heightened awareness of the dangers to the human habitat from global warming. The assessments of climate scientists increasingly express a sense of urgency that carbon emissions be reduced immediately. More and more people understand the threat. Polls show stronger understanding of the threat and a demand for governments to act to reduce carbon emissions. In some countries government action has already made significant progress; in others, sections of business are resisting or slowing down the process.

The mass sentiment has also manifested in demonstrations and mobilisations, often with high school students in the vanguard. The sentiments and general demands of these movements, including in Australia, can be summed up as: climate action NOW – with a big emphasis on NOW – no delay!

The majority of scientific opinion is that there is still time to either halt or significantly slow down global warming if there can be a large reduction in carbon emissions in the near future combined with some carbon draw-down (like planting trees and restoring wetlands). There is no serious scientific opinion that questions this technical possibility. Further, the technical capacity to go to 100% renewable electricity generation and electrify most transport already exists.

Electricity and transport combined account for around two thirds of Australia’s domestic emissions. The other third comes from industry, agriculture and everything else. There is also existing and developing technology for significant reductions in emissions in all these other areas. Australia also contributes significantly to global emissions through its export of coal and gas.

The obstacles to rapid transition to renewables are not technical but political. Powerful sections of capital – in particular, that section of capital still based on the production and sale of carbon (coal, gas, oil) – is either outright resisting the transition or trying to slow it down so as to minimise their financial losses. Both straight resistance as well as slowing down the transition to renewables equally threaten a transition that is quick enough to arrest global warming.

In thinking through any political strategy to win the most immediate and urgent changes – transition to 100% renewable electricity, extensive electrification of transport and phasing out the coal industry – it is necessary to make a hard-headed assessment of the strength of coal capital in particular and fossil fuel capital more generally. Especially in Australia, where coal has loomed large in the country’s economic history, to build an effective movement that understands the obstacles and what is feasible, it is important to study and think through this issue deeply.

The view presented in this analysis is that coal capital and fossil fuel capital is not all-powerful and can be defeated – even while the capitalist class remains in power. The argument will be made in response to two articles recently published in Marxist Left Review (MLR) which argue the opposite. The implications of this analysis for what the climate justice movement should be doing is addressed in the final section.

Liddell coal fired power station located in the Hunter Region, NSW was commissioned 1971-73. It is Australia’s oldest and one of its largest electricity generators.

Critiquing these articles is useful for two reasons. First, the articles argue their case with a very serious intent and their argumentation covers both economic and political questions and thus provides a basis for a critique that can help us understand the situation more clearly. Second, MLR is published by Socialist Alternative, a large and serious socialist organisation in Australia, which has been playing a significant role in the climate justice movement. Their ideas are circulating in the movement now and in real time. If they are wrong or have serious limitations, these need to be brought out sooner rather than later.

The first article, published under the pseudonym Catarina Da Silva, Fuelled by coal: Piercing the mirage of a sustainable capitalist Australia, argues that coal is so important to the Australian capitalist class that capital will never agree to any serious moves to transition to renewables:

“The centrality of coal to Australian capitalism means that the capitalist state will always serve the needs of coal. The Australian state is not going to be persuaded to abandon a multi-billion dollar export industry, even under the weight of an increasing climate crisis. This is particularly the case because of the fact it is an industry linked to imperialism and therefore of central importance to global capitalism.”

“Any abandonment of the fossil fuel industry in economies ‘blessed’ with access to these natural resources will not come within the framework of capitalist social relations. In a world structured around profit and the accumulation of value, Saudi Arabia and the USA won’t give up oil, and Australia won’t give up coal. Achieving that will require more than merely electing left wing figures to positions of power, and more even than mass movements to put pressure on a capitalist government. It will require the total dismantling of capitalism.”

The second article New movement, new debates: The contested politics of climate change by Sarah Garnham has a very similar position. She finds,

“For capitalism, fossil fuels are not an addiction, they are oxygen”

“…things like 100 percent renewables, no new coal and zero emissions. These demands cannot be granted under capitalism…”

“…the system itself could not survive if the transitions necessary to solving the climate crisis were carried out. For capitalism, fossil fuels are not an addiction, they are oxygen.”

However, Garnham’s work is principally about the implications of this analysis for the growing movement. Hence, the writer only makes very brief attempts to substantiate these views (instead referring readers to Da Silva’ work).

Where Garnham try to substantiate her view on the most critical issue – carbon emissions – she does so within a short section entitled “Is a green capitalism possible?” This draws heavily on a Swedish academic Dr Andreas Malm of the Lund University. But Malm’s major book, Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming (2016), focuses mostly on the rise of steam (coal) power, especially in England 1825-1848, not whether or not coal or fossil fuels are replaceable today. Never-the-less Garnham concludes:

“Malm summarises it well: ‘The fossil fuel economy is the energy basis of bourgeois property relations’. While other materials become physically embodied in specific commodities – leather in boots, raw cotton in textiles, and so on – coal, oil, and gas are ‘utilized across the spectrum of commodity production as the material that sets it in physical motion. Fossil fuels are the general lever for surplus-value production’.”

Leaving aside any theoretical issues, practically, Malm’s formulation merely raises the question why other sources or energy cannot become “the energy basis” of a lower carbon capitalism. Electricity is also “utilized across the spectrum of commodity production as the material that sets it in physical motion”. So what stops capital from further switching out the coal and gas electrical generation for wind and solar? Obviously capital has started to do this to some extent. Why can it never be forced to do it more and faster? Garnham doesn’t address this issue – which seems to be the central issue – but concludes,

“This also means that any growth under capitalism involves the growth of the fossil fuel industry. This has been true since the early 1800s, hence Malm’s suggested general law: ‘Where capital goes, emissions will immediately follow. The stronger global capital has become the more rampant the growth of CO2 emissions’.

Given this, it is impossible for another commodity to replace fossil fuels…”

Conflation of coal with fossil fuels in general

As quoted above, Da Silva argues, at least in summary, that “Australia won’t give up coal”. However (perhaps due to the actually weakening economic position of coal, as we will see below), the writer continuously conflates coal with fossil fuels more generally and sometimes even with the entire mining sector. So it’s not clear if Da Silva is arguing if the coal industry alone is indispensable to Australian capitalism, or if its fossil fuels in general. One example of this conflation reads:

“What the mining tax debacle demonstrated is that as long as society continues to be organised around the interests of capital, there will be a strong drive to utilise the vast coal wealth that lies beneath the Australian soil.”

But the “mining tax” – i.e. the Minerals Resource Rent Tax (MRRT) introduced in 2012 – was a tax on all mining, not even just fossil fuels, let alone just coal. So why its failure could demonstrate that “as long as society continues to be organised around the interests of capital, there will be a strong drive to utilise the vast coal wealth that lies beneath the Australian soil” is left a mystery.

Garnham starts from the slightly more realistic suggestion that fossil fuels are indispensable to capitalism, not that coal alone is. However, that article also slips into conflating fossil fuels as a whole with coal. For example talking about the latest anti-protest laws targeting environmentalists, Garnham says,

“These harsh responses to what is, at this stage, a very liberal movement with considerable popular support is an indication of how desperately important it is for the Australian ruling class to defend the coal industry.”

The difference between environmental sustainability and reducing carbon

A further conflation runs through both of the articles and confuses the analysis. The two very different things are:

1.) whether or not capitalism can be made environmentally sustainable

2.) whether or not capitalism can be made to significantly reduce its carbon emissions (whether from coal, gas or oil).

We can agree with both writers that capitalism can never be environmentally sustainable, will always and inevitably act to destroy the environment, that the only possibility of environmental sustainability is replacing the capitalist system with social ownership and control (socialism) BUT completely disagree that capitalism can never be forced to make concessions to a mass movement, no matter how strong – i.e. that it will never grant reforms that slow and reduce that destruction by replacing one energy source with another.

For example, as noted above, Garnham’s brief treatment of whether carbon emissions can be reduced is in a section entitled “Is a green capitalism possible?” which starts out with a reference to Marx and quotation of Engels saying it is not. The writer also groups actual emissions reductions and green-washing (i.e. capital or governments pretending to do something) into the one category – implying that only green-washing really exists.

Da Silva conflates the two issues even in the title of her article, “Fuelled by coal: Piercing the mirage of a sustainable capitalist Australia”. The implication might be that if we reject Da Silva’s argument that Australian capitalism cannot quit coal then we believe that capitalist Australia can be environmentally sustainable.

The title refers to “sustainable capitalist Australia”, but the core argument in the article is specific to carbon emissions. As above, Da Silva argues that coal in particular, and also fossil fuels more generally, are so central to Australian capitalism, and offer it such enormous profits and competitive advantages, that the Australian capitalist class will never be able to give them up, no matter how much mass pressure they come under.

Yet Da Silva does not make a convincing argument for this conclusion. In particular, in the case of thermal coal, widely available information clearly point in the opposite direction. Coal is not indispensable for Australian capitalism. It is demonstrated below coal has already begun its exit. The real issue is not if capitalism can be forced to abandon coal but how long the transition takes. Giant wind and solar farms or electric cars are no less capitalist than coal or oil – even if the popular imagination does not yet view them as such.

If the MLR is right and coal is here to stay as long as capitalism, obviously that has the most serious implications for what the climate justice movement should try to achieve and how. It would be dishonest to working people, for example, for the movement to “demand” the government roll out 100% renewable electricity because we would be pretending to ask for something we really think is impossible. This is why we need to understand the issue clearly.

Is Australian capitalism hooked on coal?

It is certainly true that coal played an irreplaceable role in the historical development of Australian capitalism and remains a large and important industry today. In the 2017-18 financial year, there were 38,100 people employed in coal mining and no doubt many more in transport, power and related industries. Last year coal remained by far the largest source of power to Australian electricity grids generating around 60% of all electricity. In 2018, the total value of coal exports was AUD$67 billion. That is 3.5 per cent of GDP. In 2017 coal made up 14.8% of total exports. At the inflated prices received in 2018, both thermal and metallurgical coal exports each earned more than any other export except for iron ore.

Peak Downs, is a large open cut coking coal mine, one of seven owned by BHP Mitsubishi Alliance (BMA) in the Bowen Basin, Queensland.

In this context we might expect to see powerful coal companies dominating the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX). But the opposite is true. The only non-diversified coal company in the top 100 (ASX100) is Whitehaven Coal which is ranked number #99 and makes up 0.16% of the index’s value. The other ASX100 companies that mine coal are BHP, South 32 and Oz Minerals – all multinational diversified minerals companies that earn most profits a from a range of minerals besides coal.

South 32 is ranked #32 and makes up 0.77% of the index. It exited thermal coal in 2019. Oz Minerals is ranked #93 and makes up 0.2% – but most of its revenue is not from coal. BHP, is the largest mining company in the world and the third largest listed Australian company surpassed only by the Commonwealth Bank and CSL. BHP makes up some 6.6% of the index. However its thermal coal assets (which are located in Australia and Colombia) were expected to generate just 4 per cent of underlying earnings in 2019. According to a research paper published in 2017 BHP’s total Australian based coal income (A$5.2 billion) made up 23% of its reported Australian revenue (and therefore much less of its global revenues). Rio Tinto and Wesfarmers have already entirely divested from coal and a string of reports published in the middle of last year suggest BHP too is looking to divest from thermal coal.

BHP warned its investors that coal could be phased out “sooner than expected’. The company says it has “no appetite for growth in energy [thermal] coal regardless of asset attractiveness” – i.e. it has no appetite to acquire even the most profitable thermal coal mines. Neither does Glencore, a Swiss-based company which is Australia’s biggest coal miner. It announced it would cap coal production at current levels. Anglo American and other large international diversified mining companies are also indicating they plan to sell off thermal coal assets.

For better positioned, diversified companies, according to the Wall Street Journal:

“these relatively unimportant [coal] assets come with outsize political risk. Coal producers face not only the risk that investors eyeing so-called environmental, social and governance benchmarks will desert them today, but also the possibility that a tougher global carbon regime could crush profits in the not-too-distant future.”

The relative absence of coal from the upper echelons of the ASX reflects that the capitalist class has come to view coal as a second class commodity – second class that is, in terms of profits. As a result coal is increasingly mined by smaller, second tier companies while the powerful multinational diversified mining corporations such as Rio, BHP, Glencore and Anglo American seek either to divest or hold only the top class (i.e. most profitable) coal assets as a minority of their overall portfolio.

Tax

From a government point of view coal is no more indispensable. The Australian Federal Government budget for the financial year 2019-2020 is just over 500 billion dollars. Only a little over 10 percent of this – so just over 50 billion – came from the top 2200 corporations. The Australian Financial Review reported in December 2019 that in the previous financial year

“The big four banks, Telstra and mining giants BHP and Rio Tinto are the nation’s biggest taxpayers, with new transparency data showing the 10 largest firms paying $23 billion to the ATO.”

So, besides these 10 corporations, all of the other 2190 corporations combined seem to have paid around $30 billion between them. How much of this came from coal? Likely a completely negligible amount. It seems coal contributes just a small fraction of 1 percent of the federal revenues.

Certainly any lost tax revenues from a coal phase out could be easily replaced, even if coal was not replaced by other taxpayers – such as capitalist wind farms. The same report quotes shadow assistant treasurer Stephen Jones,

“while the average single Australian worker pays 25 per cent of their income in tax, large companies earning over a billion dollars averaged tax payments of only 2 per cent of total income”

Indeed. Raising corporate tax, for example from 2 to 3 percent of income, would more than offset closing down coal mining. Moreover, the subsidies given to the ageing and inefficient coal industry may well exceed its tax payments. Even in regions where coal is concentrated, it still makes up a small portion of overall economic activity and tax. For example coal royalties made up just 2% of NSW govt. revenues in 2013-14.

Coal jobs

Da Silva argues that,

“Counting dependent industries, mining is still only responsible for slightly less than 4 percent of workers employed in Australia”

Here again we have the conflation of coal with the whole mining sector. The article is asserting that coal not “mining” (i.e. all mineral extraction, like copper, gold and so on) cannot be shut down under capitalism. Also, the phrase, “dependent industries” is misleading. All economic sectors create “dependent industries” or related jobs. That is no more the case for mining coal as it for building solar farms or pumped hydraulic energy for example.

According to ABC fact Check, in the 2017-18 financial year, there were 38,100 people employed in coal mining. Only slightly later, in 2019, the total number of employed workers in Australia was 12,958,700, meaning only around 0.29% of all jobs are in coal. This compares to 6.8% in manufacturing, 9% in construction and 13.3% in healthcare.

Even in Queensland and NSW – where around 90% of Australian coal mining occurs – the situation is hardly overwhelming. According to a 2016 report by the Australia Institute,

“The coal industry has always been a minor employer in Queensland. At its peak it employed fewer people than the arts and recreation industry, but in recent years has shrunk further, shedding 10,000 jobs in Queensland and now representing less than 1 percent of the state’s workforce.”

In NSW Coal mining employs less than half of one percent of the workforce – though in the Hunter valley the figure is five percent. Yet coal will not be simply shut down. It will have to be replaced. Employment in renewables is already beginning to rival coal. According to the ABS there were 17,000 full time equivalent jobs in renewables in 2017-18. The total number employed must be well over half of the 38,000 jobs (not all full-time) in coal.

Coal fired power in Australia

The real argument in relation to electricity in Australia seems to be not so much if coal can be replaced as a power source but when, and what will replace it.

Da Silva claims that Australian electricity, like the capitalist economy as a whole, is built around coal and therefore, it is unrealistic to believe coal can be removed from the grid. But to make this claim the writer quotes the long outdated 2010 Gillard government report. Da Silva says,

“Around three-quarters of Australia’s electricity supply comes from coal, compared to 38 percent of global electricity supply. The Gillard government attributed this to the ‘large, low-cost resources located near demand centres and close to the eastern seaboard’.”

On all three major electricity grids on the Australian mainland, Da Silva says,

“electricity supply is quite literally built around coal supply, and a significant expansion and redevelopment of Australia’s energy infrastructure would be required for any substantial shift away”.

“The Gillard government argued that major impediments to shifting to renewables included ‘higher costs relative to other energy sources, their often remote location from markets and infrastructure, and the relative immaturity…of many renewable technologies’.43“

“it would require a massive investment in energy infrastructure that is inconceivable in the current political context. In any case the political impetus is not towards renewables: early in 2019 it was revealed that the rate of investment into large scale renewable projects has declined significantly since 2016.44“

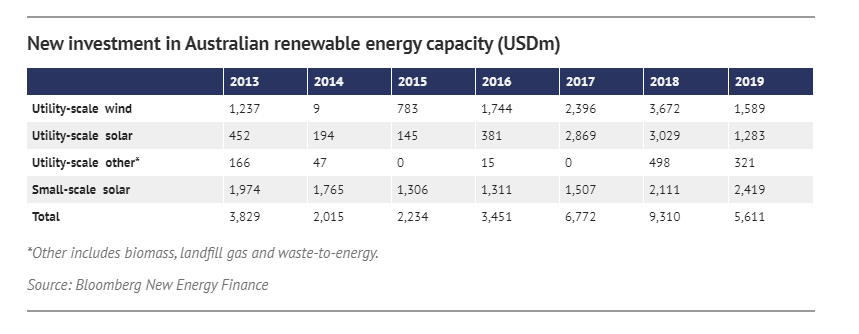

This is all factually wrong. For example, the writer says renewables investments has declined since 2016. Actually, it increased. Da Silva misread the source article which actually says “new investment committed in the first half of 2019 has fallen back to 2016 levels”. Investment was higher in 2017 and 2018 than it was in 2019. Yet all three of these years were higher than 2016, as can be seen (figure 1). The trajectory of renewable power has been not down but up, even if, as the Guardian notes, the speed of uptake has slowed under the anti-renewable federal government and its energy policy paralysis.

(By saying that the necessary investment is not conceivable “in the current political context”, the author also avoid addressing a situation where the political context changes, i.e. with the growth of a mass movement.)

Figure 1.

Since that article the policy paralysis has worsened. Now there are a significant number of newly built solar and wind farms, especially in Western Victoria and NSW that are ready to be plugged into the Eastern States’ grid but are being held back by the regulator, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) due to unresolved “grid stability” issues the federal government refuses to address. The result is long delays and high costs for capital invested in these energy farms and a downturn in the rate of new investment, at least until the technical and regulatory hurdles are resolved.

However, even a much slower rate of investment in new renewable generation capacity far exceeds investment in new coal power generation – which is ZERO dollars. It also exceeds new gas which is mostly limited to gas “peaker” plants used during demand spikes but too expensive for ongoing supply. The trend, clearly, is towards renewables. If there is zero investment in new coal, then sooner or later coal will no longer supply electricity. For example AEMO thinks two thirds of Australian coal plants will be gone by 2040. The idea that it is impossible to accelerate these existing processes – even under the pressure of a mass movement – is not supported by facts.

Renewables supplied just over 20 percent of Australian electricity on an annualised basis in 2019. They supplied greater than 50 percent of the National Electricity Market (for ten minutes) for the first time in November 2019. Renewables share will continue to increase as the existing pipeline of already built and under construction renewables continues to come online. Coal’s share has already dropped to around 60% down from its peak of 84% in the late 1990s according to Morison Government figures. In aggregate, annual domestic coal consumption since 2015 (average around 122Mt) has declined by around 11 per cent since the mid 2000s.

Low cost renewables

The problem is not – as the Gillard Government reported over a decade ago – that renewables in Australia have “higher costs relative to other energy sources” – the costs are low and falling. The most authoritative study of energy generation costs in Australia was released by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and AEMO – both federal government agencies – in 2019. The report estimates the average “levelised cost” (which includes cost of construction, finance and everything else) of newly built wind energy to be $45 per megawatt hour, solar to be $53/MWh while coal averages a whopping $145/MWh for black coal and $181/MWh for brown!

Coopers Gap 543MW wind farm has 124 turbines and is located on farmland around 250kms North West of Brisbane.

The cost of producing electricity at existing coal fired power plants is of course cheaper than building new coal and it is this cost that is competitive with building new renewables. The fight is really over how long existing coal plants should be kept online. However, even existing coal is in some cases becoming more expensive than building new renewables. Nine of the 12 large coal power stations in Australia are over 30 years old. Their rising running and maintenance costs have in many cases either already passed, or will soon pass the cost of building new renewable capacity.

Take the example of AGL’s 50 year old 2000MW Liddel coal fired power station in NSW – one of the largest and oldest in Australia. The company announced Liddel’s retirement (and replacement with some renewables, gas and storage) for 2022. After a public fight with the Federal Government the company reluctantly agreed to extend the station’s life, but only until 2023 and only part of it.

The federal government set up a task force to investigate the possibility of further extension of Liddels life from 2023 to 2026. The report leaked. It reportedly found the cost of repairs and maintenance needed for the three year extension would run to 300 million dollars!

Interviewed on RenewEconomy in November, 2019 Ross Garnaut said

“It’s not just the [low] cost of equipment for renewable energy and storage [that makes renewable power competitive – SK], the transformation or reduction of the cost of capital, when most of the new energy and the industries using new energy, most of their costs are capital costs, so the interest rates coming down to near zero radically reduces costs. […] unlike coal or gas where the current costs, the operating costs of buying the coal, producing it and buying it, are a high proportion of costs. So, the fact that the economics have moved so much in favour of the transition does mean that we can move a long way quite fast”.

Despite super-low interest rates, no capitalist or consortium can be convinced to build even a single new coal fired power station, despite the federal government practically begging for years. Why? Because coal is seen by capital as antiquated technology. Some finance houses still try to make money funding development of coal power in the Third World – as has long been the case for antiquated technology of all types – but nobody will risk a billion dollar stranded asset in Queensland or New South Wales.

Sun Metals’ 124MW Solar Farm provides electricity for the company’s zinc operations near Townsville.

This brings us to another crucial weakness of coal. It is unreliable power for capital. Coal’s reliability as a power source worsens as the existing fleet of power plants age – hardly a small issue for industrial and commercial capital. The Federal government (and Trump) spent years bad mouthing renewables as unreliable power. However such rhetoric has become increasingly unreal in the context of the regular outages at coal plants especially in Victoria’s Latrobe valley.

Infrastructure

It is true however that the transition to fully renewable electricity “would require a massive investment in energy infrastructure” as Da Silva points out. There needs to be investment in “firming”, such as batteries, pumped hydro and demand management systems. There also needs to be investments in the grid, such as new wires, to reflect that electricity is being generated in different locations and in different ways than before.

In other cases regions with existing infrastructure and skilled workers – such as the Latrobe Valley in Victoria and Port Augusta in South Australia – are also rich in renewable resources. This means that power lines running from old coal power stations can remain in use and skilled workers employed to update and maintain them.

However, even the investments required to add renewable power to new areas are far from impossible under capitalism. Again we can see this plainly because these investments are already being made (by capitalists) – albeit too slowly.

The utility scale batteries that have been installed so far in Australia have been very profitable. The most well-known example is the Hornsdale battery commissioned by the South Australian Government and installed by Tesla. This is considered by energy experts to have been extremely beneficial in stabilising the South Australian section of the National Energy Market (NEM) and has been highly profitable. Though it is not the only big battery in South Australia and more are being built. Utility scale batteries are now in operation in SA, Victoria, NSW and Queensland, with more on the way.

Besides buying energy cheap and selling it dear, batteries can accurately respond to fluctuations in power supply or demand in a fraction of a second, long before any “fast start” gas generators, let alone coal. As a result, batteries can earn hefty profits providing services that help to stabilise the grid (known as Frequency Control Ancillary Services – FCAS). Other capitalists are wanting to get in on the act. Increasingly, capitalists not only invest in stand-alone wind or solar farms but projects that combine solar and wind (or both) with batteries – that is, they invest in “firmed” renewables.

Jamestown 100MW battery is one of three big batteries that help to stabilise the grid in South Australia. It is located in the upper Spencer Gulf renewable energy-industrial hub.

One example is AGL’s recent deal for a 100 megawatt/150 megawatt hour “giant” battery to be built next to the planned Wandoan solar farm in Queensland. Another is the recently approved Port Augusta Renewable Energy Hub, a 320MW hybrid wind and solar project located close to existing infrastructure that used to serve the now defunct coal fired power plants. In the same area, the Playford Utility Battery (PUB) project has also just received the go ahead to build a large 100MW/100MWh facility.

Pumped hydroelectric power storage at this stage is still the domain of the federal and Tasmanian governments. The Snowy 2.0 project will generate 2000MW of energy and hold up to 175 hours of storage capacity. Hydro Tasmania is currently contemplating the size of a second planed inter-connector line across the Bass Strait to transmit pumped hydroelectric power generated at various sites across the state. The combined effect of these two projects alone is expected to meet most of the bulk grid stabilisation requirements for Victoria’s grid to go to 50% renewable electricity by 2030 – a legislated target.

Genex power also hopes to convert an old gold mine in Kidston, North Queensland to a pumped hydro facility next to its existing solar farm – a project the QLD state government supports. However it is waiting for a power purchase agreement before proceeding. A similar project in South Australia is currently being tendered.

Coal power overseas

The same argument – coal is indispensable – was made until quite recently about electricity generation in the United States. But that country is already well down the path of eliminating coal fired power. Despite Trump’s efforts to bring back coal, about 50 coal plants had already shut under his presidency by May 2019. Coal’s share of US generation has now declined to around 25% and continues to free-fall.

Similarly, in Europe, according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis:

“The EU reported a record slump in coal-fired electricity use in the first half of the year of almost a fifth compared with the same months last year. This trend is expected to accelerate over the second half of the year to average a 23% fall over 2019 as a whole. The EU is using less coal power in favour of gas-fired electricity – which can have roughly half the carbon footprint of coal – and renewable energy.”

Renewable electricity’s share in the US, Australia, China and India are all around 20%. In the EU it is now well over 30%. In every case the proportion of renewables is growing while, at least in the rich countries, coal’s share is shrinking.

The problem is not that Australian capital cannot shut down its coal power stations. It’s that a powerful section of capital would rather leave these existing investments operating for as long as possible before they are shut down. There is currently a wide range of views within the capitalist class about how long to leave them open or how fast the regulator should act.

Coal exports

Perhaps sensing coal’s weakening grip on domestic electricity generation, Da Silva after writing about electricity, then switches arguments. The real centrality of coal to Australian capitalism, we are told later in the article lies not principally in power generation but as an export commodity. To bolster this, the writer conflates coal with “extractive industries” of which coal is only one:

“Australia is anomalous in its dependence on extractive industry exports; proportionally comparable only to Canada and Norway among developed nations, with more than 30 percent of merchandise exports coming from fuels and minerals.”

Thermal coal

To examine exports properly we need to separate the two components: thermal coal – which is used to generate power – and metallurgical coal – a raw material used to make steel. Once we’ve separated the two we can see that thermal coal exports has many of the same dynamics as domestic thermal coal generation described above. Thermal coal for export also turns on electricity generation, this time not domestically but in Asia. And just like domestically, the real question about thermal coal exports turns out not to be, can Australia give it up? It is, for how long will thermal coal remain an important fuel source overseas?

Japan, South Korea and Taiwan between them take a large majority of Australian thermal coal exports. Japan, which buys 45%, is one of the most highly developed economies in the world. South Korea and Taiwan have more or less caught up with the rich countries in development terms. This does not bode well for coal exports because, like Australia, the rich countries as a whole are (slowly) turning away from coal for electricity generation.

Australia sells almost no thermal coal to India and surprisingly little to China, both of which source the majority of their supply domestically. The coal lobby (rather desperately) now points to South East Asia as the last possible frontier for export growth. However, the largest country in South East Asia – Indonesia – is also the world’s largest exporter of thermal coal. It also sits a lot closer to potential markets in SEA than the Bowen and Galilee Basins.

Undeniably, the coal bosses as a whole have done very well this century so far. As the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) pointed out in its September 2019 bulletin entitled The Changing Global Market for Australian Coal, exports have expanded significantly over last two decades. However there are many signs the good times may be approaching their end. The same report notes, for example, that over the latest four years (financial year 2014/15 through 2017/18) export volumes have flat lined – despite the continued economic growth in Asia.

The Reserve Bank reports,

“Investment in the sector [i.e. coal production in Australia – SK] slowed from 2012 because falling prices led to a number of projects being delayed or cancelled (Saunders 2015). Investment has remained subdued since, as firms in Australia have focused on investments to sustain production rather than significantly expand output.”

“coal’s share of global electricity generation has been declining – down from a peak in 2007 of a little over 41 per cent, to 38 per cent in 2018.”

Things actually got worse for coal the following year. According the International Energy Agency – which has repeatedly underestimated renewables rate of growth – 2019 saw a record-breaking decline in coal-fired electricity generation of more than 2.5%. But back to the RBA:

“At present, spot and contract prices exceed average variable production costs for most Australian thermal coal operations. However, Australian production costs span a fairly wide range, and some higher-cost operations may experience margin pressures if thermal coal prices were to move lower on a sustained basis.

“The outlook for thermal coal demand will largely depend on how energy generation evolves and, in particular, how fast renewable and alternative electricity generation displaces coal-powered generation.”

Growth of coal fired power in India and South East Asia “in the near term“…

“may partly offset a more general decline in demand as global electricity generation transitions away from coal to other energy sources. Over the longer term, however, the balance of risks for demand appear to be to the downside”

“Over the next 20 years, the increase in global energy demand is expected to be largely met by renewable energy sources, and by 2040 renewables are expected to account for a larger share of electricity generation than coal (BP 2019b).” [note the RBA’s source for this projection – BP!!]

“To date, the decline in renewable energy costs has been faster than expected. Should this trend continue, the substitution away from thermal coal and towards renewable energy sources would also be faster.”

“Although there may be some scope for incremental increases in production at existing operations, there is relatively little additional capacity likely to be added to the seaborne market, given current indications of global investment plans and the long lead times for expanding capacity.”

That is all in the words of the Reserve Bank of the Australia! Clearly the Australian capitalist state – far from being unable to give up thermal coal exports is planning an orderly retreat – even if they might like to draw out the timeline.

Covering the price plunge which began in 2019, the Guardian reported:

“Researchers found that China’s coal-fired power generation was flat lining, despite an increase in the number of coal plants being built, because they were running at record low rates. China builds the equivalent of one large new coal plant every two weeks, according to the report, but its coal plants run for only 48.6% of the time, compared with a global utilisation rate of 54% on average.”

In addition, much of this new plant allows China to retire older, less efficient plant and hence does not increase coal consumption. The reason China is important is because as the largest global consumer: what happens in China impacts world price – even if most Australian exports go elsewhere.

Australia’s major thermal coal markets: Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and China are all declining. Japanese coal imports were boosted in 2012 and 2013 following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor meltdown which precipitated the near total phase-out of nuclear power. However Japanese coal consumption and imports started to flat line around 2013-14 and then began to decline.

South Korea too has already begun moving away from thermal coal. Its imports from Australia peaked in 2015 and it has only one new coal power plant in development. Taiwan has no new Thermal coal plants under construction or planning.

India, which was vaunted by the coal lobby last year as a bright hope for Australian thermal coal, takes around 3.5% of Australian exports. India supplies around 80 percent of its thermal coal domestically and aims to rapidly increase domestic production to meet all or almost all of its needs. It also has relatively large renewable energy targets (currently renewables account for around 22% of electricity) which, as these are ramped up, will dampen any prospects for thermal coal imports.

The coal bosses last hope it seems is (or was) South East Asia which is both close and, they hope, undeveloped enough to keep building coal fired power plants. Like China and India, most of SEA’s rapid growth in electricity demand between 2000 and 2017 was met by expansion of fossil fuel generation and coal in particular, while renewable expansion could not keep pace. However, in 2018 work on new coal power capacity in SEA fell to 79% below its 2016 peak. The first half of 2019 witnessed a continuation of the investment slump. The renewables sector in the region, besides hydro power, is relatively undeveloped but it is now growing quickly from a low base.

Investment slump

Perhaps most clear evidence of thermal coal’s decline in Australia is the investment slump in new production capacity. The RBA identifies a sustained slump from 2012 onwards,

“Information from the Bank’s liaison program suggests that the changing outlook for prices for metallurgical and thermal coal has been a factor weighing on producers’ investment decisions to expand capacity. […] investment decisions are based on long-run price expectations,”

“Funding availability has also been noted as a constraint on investment, as banks are increasingly reluctant to finance coal developments; most new finance is being secured from consortiums of lenders, which can be more complicated to arrange.”

Most telling, the investment slump occurred alongside hugely inflated prices (From 2016 through mid-2019 coal prices were very high, see figure 2). Yet even in this period, capitalists, while happy to pocket windfall profits, or perhaps invest in maintenance or marginal capacity increases, evidently didn’t believe the good times would last (in coal) and rarely invested in new thermal coal mining capacity.

Figure 2

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia, 2019, p33.

The Department of Industry documents the same phenomena. According to the Resource and Energy Quarterly, December 2019, investment in coal exploration declined sharply from a mid 2011 peak (when prices also peaked) to mid-2015 (figure 3). Since then exploration and investment has remained low, averaging less than 50 million AUD per year despite another huge (temporary) price bonanza that occurred 2017-2019.

Figure 3

Australian coal exploration expenditure and prices

Source: Department of Industry, 2019, p51.

While the large investments made around 2011-12 did achieve increased export volumes the following year or so, since then thermal coal export volumes have flat-lined (figure 4).

Figure 4

Australia’s Thermal Coal Exports

Source, Department of Industry, 2019, p50.

The Department of Industry projects that, in value terms, thermal coal exports will be eclipsed by gold in FY 2019-20 ($20.8 billion versus $27.8 billion) and then keep falling the following year. Indeed for many of the mines with higher production costs, the retreat from the sector threatens to be less orderly than they might hope. In September, 2019 an Australian Financial Review article entitled Price slump threatens viability of coal projects reported that

“Billions of dollars worth of Australian coal projects are under threat as slumping prices render about 19 per cent of the world’s existing seaborne thermal coal supply loss-making.”

“Adani’s Carmichael and Whitehaven’s Vickery mine projects were lucrative proposals in mid-2018 when thermal coal prices soared to six-year highs, and while both companies remain confident, analysts say a sharp slump in prices has challenged the projects’ viability.”

“Most big Australian coal miners (all of whom have shorter haulage distances to port than Adani) struggle to profitably produce coal for $71 per tonne”

In what is likely a sign of things to come if low prices are sustained, the Cook Colliery was shut down by its receivers in December.

It’s not that rapid growth of renewables is significantly displacing coal in Asia. New renewable capacity is not being added fast enough to do that yet. What is happening is the cheaper renewables and gas, falling economic growth and rising coal costs, often ageing facilities and opposition to new coal all combine to choke it off – though, at this stage, far too slowly.

Big capital can see the writing on the wall. ANZ is the principal financial backer of coal among the four giant Australian banks. However an internal email from July 2019 shows the bank “will shed more than $700 million of thermal coal loans by 2024 – a reduction of 75 per cent” or even “accelerate this timetable”. ANZ describes this as their “orderly thermal coal mining reduction strategy”.

Internationally, in the latest in a string of similar announcements, Goldman Sachs, “has now ruled out future thermal coal financing, either for new mines or power stations globally.” Blackrock, the world’s largest investment house, announced it would radically reduce investments in thermal coal. These could be described as strategies for “orderly” (read profitable) retreat too. Goldman’s resolution deals only with new coal, while Blackrock’s only applies to companies with a greater than 25% exposure to coal. These announcements won’t bring down the house, but they do indicate which way the wind is blowing.

Metallurgical coal

Metallurgical coal on the other hand, will likely be around for much longer then thermal coal. Though that would likely the case even under socialism. Even with a socialist state in all the major countries, it would probably still take considerable time to eliminate metallurgical coal internationally.

Australian coal exports are divided fairly evenly between thermal and metallurgical coal. In 2018 just over 200Mt of thermal was shipped compared to around 180Mt of metallurgical coal. In terms of price, Metallurgical coal, depending on the grade, typically sells for double that of premium thermal coal. So metallurgical coal’s share of export income and profits is bigger. Therefore, for economic reasons as well as technical, metallurgical coal may be a tougher opponent of the mass movement than thermal.

But globally metallurgical coal represents only 13 per cent of total coal consumption. So even in the worst scenario, where metallurgical coal continues more or less at current levels decades into the future, it still makes absolutely no sense from a climate point of view to argue that the coal industry as a whole cannot be shut down. If the other 87% of coal consumption can be shut down – or largely so – then we have to fight for that to happen, not proclaim it impossible.

Metallurgical coal, as mentioned is in a different situation to thermal coal as far as its profitability is concerned. While, the metallurgical coal price does tend to move up and down together with that of thermal coal it, it does so at a higher level. The RBA comments,

“In the metallurgical coal market, in contrast [to thermal], margins are currently strong, with average variable production costs for most Australian and other global operations below prevailing spot and contract prices.” […there is also] “a more positive medium-term outlook for demand (DOIIS 2019b).”

Looking at price, the RBA says

“Chinese annual steel production appears to be broadly around its peak and production is expected to gradually decline” […] “The Chinese Government has a target of increasing the share of scrap steel used in steel production to 30 per cent by 2025” [as more of the steel consumed in China over the last few decades becomes ready to scrap – SK].

Again, China is not the main buyer of Australian metallurgical coal – India is. However, as the dominant global consumer, what happens in China affects price, which is expected to drop. The Department of Industry expects the value of Australian metallurgical coal exports to fall to less than half that of iron ore. In 2019 it had already fallen below both iron ore and LNG. While metallurgical coal remains a lucrative export industry for sections of Australian capital, it hardly seems so dominant that the ruling class as a whole could never be forced to shut it down – even in the face of a powerful mass campaign.

Natural gas

Perhaps more problematic than coal, at least politically, is the steady expansion of Australian natural gas extraction and exports, as well as the push for increased domestic consumption. Several massive LNG export projects were constructed relatively recently and have potential technical and economic lives extending much further into the future than Australia’s fleet of ageing coal power stations. Further, SANTOS and other gas giants are seeking to complete projects that would pose a similar threat in domestic electricity production.

Chevron, Shell and ExxonMobil – the owners of the massive Gorgon LNG complex on Barrow Island in North West WA – managed to build and start exporting gas while much of the public was still dazzled by the industry propaganda of “clean” gas and before the climate justice movement had become a mass phenomenon.

The Location of the Gorgon/Barrow Island Liquefied Natural Gas project and some of its gas fields. It is principally owned by Chevron (47.3%), Shell (25%) and ExxonMobil (25%).

LNG extraction at Gorgon, North West Shelf, Curtis Island, Gladstone, Ichthys and the other existing mega gas projects has been one of the main drivers of Australia’s increasing domestic emissions over the last few years – and that’s even before the gas is burned (overseas) during its final consumption. This occurred over the same period that emissions from domestic electricity production marginally declined.

There is also a large number of new gas infrastructure projects variously in exploration, planning, approvals or construction stages. These need to be fought tooth and nail. There is no inevitability about which among this pipeline of projects – if any – will go ahead. Some merely exist on corporate wish lists at this stage. The gas price, which is determined internationally, has also declined recently. If sustained, low prices may delay or destroy many high cost projects. Others may become marginal – and with mass opposition, become unviable.

To demonstrate just how not-inevitable this development pipeline is we can look at what BHP says. BHP is invested in gas exports through the North West Shelf. The company’s chief financial officer, Peter Beaven warns,

“there’s a possibility that gas will be leapfrogged by emerging markets as they opt for renewable energy”

We can take from this that there is also a large possibility that a similar “leapfrog” might occur in rich countries – like Australia. Indeed Australia doesn’t appear to have any cheap gas development options for the main Eastern States gas market. Of course that fact doesn’t stop gas companies making a play for that market and enlisting the assistance of the Federal Government in doing so.

A recent deal between the federal and NSW governments will see federal subsidies of up to 2 billion dollars for the mining and delivery of an extra 70 petajoules of gas (supposedly for the East coast market), as well electricity grid upgrades, some new renewables and securing coal supply to the Mount Piper power station. Currently NSW consumes around 120 petajoules of gas annually. According to Morrison,

“There is no credible plan to lower emissions and keep electricity prices down that does not involve the greater use of gas as an important transition fuel,”

Morrison and other backers of the deal have not yet revealed where they plan to get the gas. However, activists from Lock the Gate and others conclude the deal must involve SANTOS’ proposal to Frack the Pilliga State Forest near Narrabri in central NSW. The fracking project, which will require huge quantities of water, is opposed by local agribusiness, environmentalists and many others. Responding to environmentalists claim the deal is to frack the Pilliga, NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian said,

“We have two or three options before us including terminals, import terminals at Port Kembla and potentially Newcastle in addition to the Narrabri project … one of those three things will satisfy our arrangements”.

The Pilliga forest is also highly significant as the last remaining inland (semi-arid) forest. It is widely recognised as highly biodiverse, containing some 300 native animal species according to tourism promotional material produced by the local shire.

LNG importation on the other hand assumes federal and state governments are able to defeat local climate justice movements in Illawarra or Newcastle and nationally. This will be more difficult owing to the complete irrationality of the proposal. LNG is one of the most carbon intensive forms of energy production. It is worse than piped gas because of the power involved in the liquefaction process. Plus it is shipped. Then there is the “fugitive” gas released during fracking. A similar proposal for Melbourne’s Western Port – currently under consideration by the state Labor government – is also hardly guaranteed to defeat the considerable opposition to it.

As mentioned, it will likely be far cheaper, especially in the long run, for Australian capital to build renewable power generation and infrastructure than having to pay for imported LNG or to be constantly searching for, extracting and transporting ever greater quantities of gas indefinitely into the future – even if this were possible. A whole series of studies make this point. Bloomberg New Energy Finance, for example, predicts gas generation in Australia will fall from its current 11% to just 4% of electricity production by 2030.

Once again, the real issue seems to be not whether a transition from coal to renewables is possible, but when and how fast renewables can or should be built.

Electrification of transport

It might be argued that even if electricity is supplied 100% from renewable sources this would still not radically reduce carbon emissions because electricity only amounts to around one third of total Australian (and world) greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Another one third comes from transport and the other third comes from a combination of industry, agriculture and all other sources.

Obviously, even if only one third of GHG emissions could be eradicated under capitalism that would still be a very worthwhile thing for us to fight for and win. However, it is not only electricity that can be significantly transformed under capitalism. There is not time in the current article to outline all of them, however very similar arguments to those above could easily be made regarding the progress and potential progress in the electrification of transportation.

Every single major international car company has already made significant investments into research and development for the role out of their various new, competing electric vehicle models. Their total global investment comes to hundreds of billions of dollars and the R&D programs have been in progress for years. The reality is auto majors are scrambling to meet the (profitability) demands of the new period.

This private capitalist R&D is not for the development of new technology (electric engines are not new) but rather it is capital’s race to apply the existing technology to their own brand in a way that will sell. For example there are currently 60 models of plug in electric car currently available on the UK market with a further 34 expected in 2020. Boris Johnson recently announced the date for the final phase out of new petrol powered cars in the UK was being brought forward to 2035 from 2040 and would include a ban on new hybrid cars.

The move to electric cars (even though excruciatingly slow) reflects not only that electric engines are less polluting to the environment and public health than petrol power, they are also far more efficient and for this reason will (sooner or later) become cheaper. For the same reason, electric power will come to dominate commercial and industrial transportation (likely well before cars). In some instances the transition to electric vehicles has already taken place, such as in distribution centres (large warehouses) where standard indoor forklifts are electric and have been for many years.

In transportation to, the idea that a transition to low carbon (at least in much of the world) is impossible under capitalism seems to be undermined by the fact this transition has already begun.

Is Australia ‘the Saudi Arabia of coal’?

In an otherwise informative article in Red Flag Tom Bramble argued,

“Australia is the Saudi Arabia of coal – a global powerhouse in energy production with some of the biggest and best quality coal deposits in the world.”

This comment, is aimed at convincing us of the same position that Da Silva argues – that it is unrealistic to imagine Australian capitalism without coal. But the analogy is neither accurate nor useful. The principal economic feature of Saudi oil is that it is the lowest cost in the world. It is not Saudi Arabia but Venezuela that has, for example, the largest proven reserves. However, in Venezuela to produce oil you need to dig deep underneath Lake Maracaibo and then separate the oil from all manner of waste materials. In Saudi Arabia, relatively speaking, one barely needs to scratch the surface of the earth to get a torrent of better, cleaner stuff.

Having the best quality reserves means that whatever the world oil price is doing Saudi production is always profitable. Any time the oil price lifts above its rock bottom, Saudi production becomes super profitable. As we’ve seen this is not the case for Australian thermal coal. As the RBA notes, Australian coal production has a wide range of production costs. The worst ones are already going to the wall. But even the best ones enjoy nothing like the position of Saudi oil. This is because the commodity of thermal coal itself is increasingly uncompetitive. When it becomes absolutely uncompetitive, even the best (cheapest) thermal coal deposits will not bring an adequate return.

The analogy is a little more accurate in relation to metallurgical coal and natural gas. However making the argument that “Australia is Saudi Arabia of metallurgical coal and LNG” is far less likely to convince anyone that any reform is impossible short of socialism.

Bramble continues

“The large quantities of fossil fuels in Australia is one of the country’s main competitive advantages”

That is a fair comment. Yet Australian capitalism’s principal competitive advantage – like that of all rich countries – is not found in its soil, but in its exceptionally high labour productivity. That is a large part of the reason why, for example, Australian coal, iron ore and other mineral production is low cost. It not just the lay of the land but also the application of driverless trucks, trains and all the rest that brings costs down.

Yet this exceptional labour productivity can be turned just as easily wind power, solar, batteries and hydrogen as coal mines, fracking and offshore oil. These promise equally mouth-watering profits as oil gas and coal. Labour productivity explains why Australia, indeed every First World country, is far richer than Saudi Arabia.

It is true that Australia – an entire continent inhabited by less than 30 million people – is very well endowed with natural resources (far beyond those necessary to support such a small population) and hence has large exports. But these natural resources exist not only below the soil as fossil fuels. There is also gold, diamonds, iron, copper, rare earths, fish, forests, fields and almost everything else you can think of… including sun and wind… and lots of it. In industry speak, Australia possesses “world class” sun and wind “resources” – and there is more than a few capitalists keen to exploit them.

As renewable power increasingly becomes the cheapest power source this will provide especially lucrative advantage for Australian capital. In terms of sun radiation per square meter and suitable and available space for solar and wind farms, there is likely no developed capitalist society more advantageously placed than Australia.

While Da Silva noted than many of the sunniest spots are far from (current) areas of power use, many capitalists note that much of Australia’s mineral wealth occurs in locations highly appropriate for building solar farms next to the mines. This will allow capital to convert many mines from extremely expensive diesel powered generators, to extremely cheap solar and wind power. Further, large solar and wind can be built adjacent mines or in mining areas and cheap (almost free) electricity then used to process the minerals before they are exported. It is thought that Australian processing of minerals with large scale renewables will be cheapest in the world.

As Ross Garnaut put it on ABC radio on Jan 13, 2020

“Australia is by far the largest exporter of aluminium ores and iron ores. When the world is producing aluminium and iron without emissions, we’ll be the place that’s done.”

Asked about the prospects of Australia’s aluminium smelters Garnaut argued “each of the big smelters in Australia will face big decisions”. Bell Bay, the oldest smelter has a good future because Tasmanian wind power and hydro provides “a really low cost reliable power that will be very attractive to energy intensive industries.”

“But our big aluminium smelters in Gladstone, Newcastle and Portland are all based on high cost coal. They are all beneficiaries of Government arrangements [and] of power contracts signed some time ago. There is no prospect of coal based power being anything like globally competitive when the government subsidies go or the old contracts are renegotiated. So those three smelters are gone unless we do things differently. But the good news is… a bit of innovation could lead to globally competitive supply of power based mainly on solar and wind firmed in different ways in different places…”

The “innovation” Garnaut refers to here is that required to work out the cheapest firming in each location. If the necessary investments are made to produce power cheaply in this way, “those places will not only survive but expand”. The biggest factor according to Garnaut is the cost of capital. He says with guaranteed revenue (i.e. power purchase agreements) the cost of capital is driven down by 20%. Of course with government backing this could be generalised or driven down further.

Ross Garnaut is an academic and sometimes company director and consultant to various Labor governments. Macquarie Bank on the other hand is at the core of the Australian capitalist class. Together with the large multinational wind company Vestas, it is backing a gigantic energy project in the Pilbara: The Asian Renewable Energy Hub – a proposed combined solar and wind farm complex with generation capacity up 27 Gigawatts (50 terrawatt hours annualised – greater than total consumption in Victoria in 2017) and 50 year design life. The Renewable Energy Hub would provide energy to the Pilbara mining region and export the rest as “green” hydrogen.

Fortescue Metals, among the leading producers of iron ore in the world, and also based in the Pilbara, is an early adopter of renewable power for its mining operations. The company recently announced the addition of 150MW of solar power a second “big battery” and additional 257 kilo meters of power line bringing its Pilbara operations under one grid mostly run on renewable power.

As a company spokesperson puts it,

“The lack of an integrated transmission network in the Pilbara has been a key barrier to entry for large-scale renewables and Fortescue’s investment will address this issue.

“By installing 150MW of solar PV as part of the Pilbara Generation Project, the modelling indicates we will avoid up to 285,000 tonnes of CO2e per year in emissions, as compared to generating electricity solely from gas.

“Importantly, Pilbara Energy Connect allows for large-scale renewable generation such as solar or wind to be connected at any point on the integrated network, positioning Fortescue to readily increase our use of renewable energy in the future.”

In South Australia Sanjeev Gupta has committed capital to rebuild the steel industry. The Whyalla Steelworks closed with the death coal fired power in South Australia. Now it is open and being rebuilt with billions of dollars of investment money flowing into cheap renewable power and storage. The principal competitive advantage according to Gupta is its access to cheap renewable power.

South Australia has already achieved over 50% renewable power and is expected to easily meet its target of 100% renewables by 2030 or before. Tasmania too is already close to 100% renewables. Both states are expected to become net (renewable) power exporters. These are examples not of “green washing” – i.e. pretending to reduce environmental destruction but not really doing so – but newer and more technically advanced capitalist production processes that are actually less destructive.

What capitalism’s ability to reduce carbon emissions does not mean

Can capitalism be made to stop destroying the planet? No

As outlined, reducing carbon emissions is not the same thing as saving the planet, or creating a sustainable version of capitalism. Is it possible to stop capitalism destroying the environment? No. Is it possible to radically reduce carbon emissions under capitalism thus buying us some more time? Yes.

Capitalism will continue to destroy the environment. Even a lower carbon capitalism will not be able to stop extinctions, biodiversity loss, land clearing and pollution. As Garnham correctly points out, this an unchangeable characteristic of a social system based on production for private profit and not for human need. But that is not the point. The most immediate, most pressing and most concrete question that we are confronted with, and the issue which is the basis for the emergence of a climate justice mass movement is not “save the planet” in general but radically reducing carbon emissions as the START of a process to halt runaway global warming.

Can emissions be rapidly reduced via market mechanisms? No

There are at least two issues here. The first is well understood. Market mechanisms force the burden of transition onto working people, in particular through anarchic, unplanned sackings. In this situation, it’s likely that affected communities will oppose the transition to renewables. Capitalist political representatives can, as they are doing now, use misinformation and scare tactics to try to forge a reactionary alliance with these workers and sabotage any transition. We need a “just transition” – that is extension of social welfare and public investment to affected communities – otherwise there may be no transition. And social welfare does not come about through the market but through government policy.

Secondly, the transition to renewable power, electrification of transport and deeper electrification of industry will require large scale investments. Much of this, especially the new infrastructural needs, is well beyond the ability of individual capitals to finance and organise. Hence it requires large-scale state involvement, even, if necessary, public ownership of energy production. There is nothing new about this. The existing electricity grid and coal power generation for example was largely built and run by the Australian state and was only privatised later.

The existing market mechanisms of a carbon price (in Europe) or state run reverse auctions for private sector development of new renewable power projects (in Australia) are working far too slowly and in a far from systematic or efficient manner. They are efficient only at ensuring profits for business.

Is capitalism capable of zero emissions? No

It is, presumably, impossible for capitalism to move to zero (net) emissions globally. This article has talked mostly about electricity and made short comments about gas and transport. There is also the other sources of GHGs, especially agriculture and other industrial processes such as steel making, cement making and so on. As mentioned, electricity is currently responsible for about 1/3 of Australian and global emissions, transport emits another one third and everything else combines to emit the remaining third (about half of which is from agriculture).

It may only be possible to partially reduce emissions from the other two sectors. Of course, nobody knows what is or isn’t possible with any degree of precision. However, we might conclude that the competition between capitals almost certainly makes zero net emissions impossible. Even so, should that stop us fighting for a radical reduction of emissions right here and now? Moreover, how does abandoning the fight for radical reductions today – which is the inevitable result of arguing that these reductions are impossible – strengthen the movement to confront capitalist power tomorrow?

Will capitalism resolve the problem of carbon emissions for us? No

The inability of market mechanisms to seriously and rapidly reduce carbon emissions reflects the reality that capitalism as an economic system is incapable, by itself, of making the necessary changes. This article does not argue that capitalism itself can reduce emissions sufficiently and rapidly but that it is possible to achieve rapid reductions under capitalism through the political intervention of a strong mass movement.

Is it possible for capitalism to switch fuel source? Yes

Capitalism is a social system based on the exploitation of workers’ labour by the private owners of the means of production. There is nothing inherent in this that says these means of production must be set in motion be a specific type of fuel source. Switching old for newer and more advanced fuel sources has been a feature of capitalist development historically. In capital Marx emphasises the replacement of water with steam (i.e. coal). In Imperialism Lenin emphasises the replacement of steam with electricity in industry and coal with oil in transport.

The 1.2 GW Hornsea One wind complex – the world’s largest offshore wind farm – is located 120 km off the coast of Yorkshire, England. It is powered by 174 turbines each 190 metres tall with a rotor diameter of 178 metres.

More than 100 years ago coal was replaced by electricity in providing direct power to industry and households. Now, it is in the process of being driven out of electricity generation – even in Australia. The idea that it can’t be or that the other increasingly technically antiquated fossil fuels – oil and gas – can’t possibly ever suffer a similar fate in transport and industry (so long as capitalism remains) is demonstrably false. We can see this, as shown, by looking at concrete evidence from the capitalist economy itself.

Renewable power, is directly imparted onto an electricity generation mechanism by the sun, wind or water. This means the fuel source does not have to be dug up from below the surface of the earth and then transported. As a result it uses less human labour. That is the essential reason it is cheaper (or fast becoming so).

Electricity (regardless of how it is produced) can be transported far more rapidly and, again, with far less labour than oil or gas which (besides being dug up) needs to be transported in trucks, ships and pipelines. That is the essential reason why electricity is cheaper – or will be.

Electric (vehicle) engines are far simpler than oil or gas burning engines. For this reason they too require far less human labour than fossil fuel powered transport engines. They are also more energy efficient.

This means that states that transition to renewable electricity and electric transport will be able to lower their capitalists’ costs (in all sectors) and increase the general profitability of their capitalist classes. This is reason demanding, say 100% renewables and deep electrification of transport and industry, is not – as both Da Silva and Garnham argue – asking capitalists to destroy their competitive position internationally.

Obviously there are large costs involved in setting up the new power infrastructure and plant (just as there are costs to capital associated with allowing climate change to go unchecked). The increasing divisions among the capitalist class appears to be over how those costs should be born, when and by who. Which classes and which sections of each class should pay. This is the situation which has evidently brought out serious divisions within the ruling capitalist class, both and internationally and in Australia. Here the most important expressions of this division are the energy policy paralysis at a federal level and ever increasing public struggle over the issue.

It is that division among capital, among its political representatives, among its intelligentsia; that lack of clarity and paralysis about what the hell to do, together with the march of climate change itself, which has created the conditions for the emergence of a mass movement in this country and around the world. That should also be the starting point from which we work out how to build the mass movement into one that can win.

What sort of climate justice movement should we be building?

When we talk about the movement “winning”, we don’t mean win overall environmental sustainability. That can only occur with the abolition of capitalism – but there is no basis, that has yet emerged, to turn the mass climate justice movement into a mass socialist movement (there is only the basis at the moment to win a much smaller number of people to socialist ideas). It is possible, with a big enough movement with the right strategy and tactics, to win the limited reforms that are already demonstrably technically feasible and there is a mass of people already willing to fight for such reforms.

These reforms are:

- 100% renewable electricity by 2030

- No new fossil fuel projects

- Phase out coal mining and exports by 2030

- Jobs guarantee with no loss in pay for all coal and fossil fuel workers

- Start the electrification of transport

- Complete the electrification of industry

These demands could be encapsulated in a struggle slogan such as: CLOSE DOWN THE FOSSIL FUEL INDUSTRY – START NOW, NO DELAY! We can and should also add important supplementary demands, as has already happened, such as “funding for Indigenous-led land management” and more.

All of these six demands are feasible under capitalism technically and politically. Demands 1,2,5 and 6 have all actually started. A movement to win all six demands would indeed confront the power of the capitalist class and challenge all those advocating neo-liberal small state ideology. Yet it would not constitute some kind of final battle to end capitalist power. If successful, it would likely weaken such power through an escalation in the struggle over what and who should determine how society is run: profit or the needs of people, including the basic essential of a survivable habitat.

To defend the planet from all forms of destruction, first we need to stop within the next few decades the processes that could destroy it by the single most pressing and imminent threat – global heating.

The Sydney climate justice action on February 22, 2020, organised as part of the Climate Justice Alliance (CJA) national day of action, brought together a large and diverse crowd.

By saying and thinking that winning these demands are impossible in the short term, it’s hard to see how activists who hold such views can genuinely fight to win them! They will of course argue at rallies, meetings and in their writings that a movement that is less than a movement to end capitalism cannot win such demands (even if they claim to support them). This is something that cannot but undermine morale and add distraction among those campaigning for an immediate start to reductions of carbon emissions.

Winning these demands will require serious struggle and the building of a powerful mass movement which makes its presence felt in all the political sectors, including – although precisely in what form is yet unclear – electorally. It will need to unite all those who are insisting on the acceleration of the transition to 100% renewables and the phase out of fossil fuels whatever their class background or other ideological inclinations.

This will all involve escalating serious ideological struggle. The transition to 100% renewables will require arguing for a government coordinating role and government investment in opposition to current neo-liberal ideological orthodoxy. Further, there will be the requirement that the government guarantee no loss in income for those dislocated by an end to coal and fossil fuels. This government guarantee of no loss of income flows from what must be grasped as a principle which cannot be compromised: if society decides that changes are needed for the good of society as a whole, then society, through the government, must be responsible that any people negatively affected be fully compensated and assisted.

Just after the 2019 Federal election the ABC surveyed 54,000 people for its Australia Talks National Survey. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, given how the election result and public views on climate change are presented in the mass media, some 72% of respondents found climate change to be a “problem personally” for them. Incredibly, only 27% of people said they were not losing any sleep over it. Even in Queensland, just 35 per cent of people said they were not losing sleep over climate change.